MEDITERRANEAN LANDSCAPE ART

Some passages from my books I particularly like…

|

|

|

|

| The Four Seasons (Vincent Motte) Click on each image to see it in full. |

|||

Manifesto for Mediterranean Gardening, published in French only, Actes Sud, 2012.

Here is an excerpt translated into English:

Ten suggestions for adapting Mediterranean gardening to other climates and today’s needs

Ten suggestions for adapting Mediterranean gardening to other climates and today’s needs

1) Observe the logic of place and take it into account when you garden: which way does the land slope, what are your local weather patterns, prevailing winds and rainfall for example. What happens to rain runoff? Do you need protection from flooding, forest fires, earthquakes or landslides? These seemingly obvious but often neglected precautions can save you expense but, even more, they can ensure long-lasting harmony in your garden.

2) When you are digging or planting, imagine what people before you have done with this land. Are there any interesting remains--old trees, stones, a hedge, a well? Or do you need to clear and clean, even deal with earlier pollution of the site? Think of the past as well as of the future of your plot, however small. What can you add to its history?

3) Get to know your existing flora and fauna, even in a town garden, from season to season. Do they vary according to exposition, altitude, competition from other species? Are some plants indicators of particular types of soil? This can help you know what to add and save expense. What species benefit from your presence? When their aims run counter to your own, can you prevent damage without eradication? Avoid stereotyping: many songbirds are actually nastier in their behaviour than cats or spiders.

4) Resist feeling guilty. If you garden with respect for other species, (including your neighbours!) you have a right to defend yourself. Gardening is a partnership but not a sacrifice. As French ecologist Gilles Clément puts it: we are all predators, and we are all prey. A garden is an homage to life but death is part of the cycle. Mediterranean cultures are rarely sentimental …

5) Useful versus ornamental: forget this outdated distinction. Instead of ornamental or even productive, think multiple ! Not just by including a bit of fashionable potager, but in the variety of the things you grow, the uses you make of them and the place itself, all day and all year long. Not only for the pleasure of the eyes, but for all the senses.

6) Give free reign to your creative impulses. In the Mediterranean tradition, hands and head are not opposed, nor are manual and mind work, no more than crafts to ‘high’ art. Designed gardens that are tightly organized around a dominant theme are no better—or worse—than those that depend on serendipity, the gifts of neighbors and of heaven. There are as many styles of garden as of poems or paintings.

7) Keep an open mind about what a garden can be. The Mediterranean mixes side by side jetset gardens, grandmother’s plots and humble allotments. No need for envy or scorn for any of these. The important thing is to make one’s own choices, not to be fashion’s slave. You can respect the logic and character of the place you live in and still be highly personal, just as you do in cooking.

8) Think local: take advantage of what you have around you. Recycle creatively, but choose materials, textures, colours, volumes that are in harmony with your environment. Avoid visual pollution. Avoid also anonymous features with no local character that can be expensive to maintain, like lawns and certain types of hedging. What plants grow well in neighboring gardens or nearby in the wild, which are typical of this place and have done well here for a long time ?

9) Think global: your choices affect the quality of water, of air and the health of future generations. You are also a caretaker in the ‘planetary garden’. As in cooking, make the most of local resources but experiment also some exotics. Different species become invasive in different environments--check with local experts. Visit other gardens, nearby or far away, you will always learn something useful for home.

10) Think slow: take time to look, sniff, taste and feel. Be open to the unexpected. Be sure there are places to rest in your garden. Lie down on the ground when conditions permit and let a cat lick your fingers. Learn to ‘touch and taste peace, silence, unmeasured time, all things which, enjoyed in their excellence, can transform you into a living being you never suspected you really were!’ (Jean Giono.)

Challenges facing landscape designers in the early 21st century

For the book Futurscapes : Designers for Tomorrow’s Outdoor Spaces by Tim Richardson, Thames and Hudson, 2011, a selection of the world’s most influential landscape and garden designers and critics were asked to respond briefly to the following simple question: "What are the greatest opportunities and challenges facing landscape designers in the early 21st century?" I contributed the following:

Many gardeners, both professional and amateur, assume their design choices are limited only by budget or personal taste. Slogans that encourage more connected vision, such as ‘Think global, act local’ and ‘Work with, not against nature’ have become merely cliché. What might they mean if we get outside the box of tired polarities: design versus plants, formal versus naturalistic, conceptual versus ecological and even culture versus nature? Why, for example, separate ornamental and useful gardening? Any one feature, any one plant, can look good but also provide food and drink, scent, health and household aids, homemade pest controls, home crafts. This kind of multiple gardening--multi-function, multi-pleasure--has been practiced for millennia as the vernacular (a term better known among architects). To paraphrase one definition of vernacular design, it is made of predominantly local materials, reveals a high regard for craftsmanship and quality, is ecologically apt, fits in well with local climate flora, fauna and way of life, is human in scale, and embodies a sensual frugality that results in true elegance. A major aim of vernacular design is climate control throughout the year—planning and planting as much for floods as droughts, regulating temperatures, providing sources of energy in the form of firewood, wind or solar power. Creativity is the essence of vernacular gardening where necessity has always been the mother of invention. Home-style ‘land art,’ appeals to gardeners of all ages. Why not bring back the energy-saving clothes line as an example of ephemeral domestic art?

The Mediterranean version is a particularly good model because, like Mediterranean cuisine, it offers infinite regional and personal variation yet is adaptable worldwide. It is locally based and economical, but capable of great refinement; pleasure-giving, healthy and accessible to all. It also lends itself to intelligent eco-tourism, playing a growing role in evolving rural economies. But there is another, deeper reason. The human footprint has been heavier in the Mediterranean than almost anywhere else in the world, and yet, recent studies affirm, ‘there is often more biodiversity in a single square kilometer in the Mediterranean than in any area 100 times larger in the northern parts of Europe’. Scientists attribute this wealth in part to ‘co-evolution’ between mankind and other species—not everywhere and not all the time, especially today, but recurrent and persistent.

One historian noted: ‘The view that humans have had almost entirely negative impacts on nature—widespread among environmental historians, historical geographers, ecologists and environmentalists—paradoxically perpetuates the old Western stereotypes of humanity as active, dominating, and separate from a nature that is passive and static. A view more in tune with late twentieth-century empirical data and current ecological theory would emphasize that relationships between humans and nature are interactive and embedded within a kaleidoscopic environment in which little or nothing is permanent.’

Multiple gardening the Mediterranean way is both very old and very new.

From The Garden Visitor’s Companion, published with Thames and Hudson, 2009.

TEN QUESTIONS TO ASK about a garden of Mediterranean inspiration

- In what sense is this garden ‘Mediterranean’?

- Has this land been used for farming? Is it still productive in any way?

- How are house and garden related by the logic of the place?

- How does this garden relate to its surrounding landscape?

- How is space organized here, and on what scale?

- What plants are used here, how and why?

- What kind of light does this garden enjoy at different times of day and year?

- Where does the water come from, how is it managed, what roles does it play?

- What is old here, and what is new? How old, how new?

- How wild, natural or formal is this garden?

1. In what sense is this garden ‘Mediterranean’?

Does it grow near Mediterranean shores or in a comparable climate zone, between temperate and sub-tropical, with long, hot, dry summers and heavy rainfall in autumn and winter (in southwest Australia, Chile, South Africa, California perhaps?) Do olive trees thrive here year round? Do citrus? Does intense, dry, summer sunshine give rich flavour to fruit, vegetables, oils and wine? Or is it a temperate zone garden where special microclimates (city courtyards for example) allow the growing of semi-hardy ‘Mediterranean’ plants? Perhaps it simply has a ‘Mediterranean’ décor—lavenders, terracotta pots—expressing holiday nostalgia? Mediterranean gardens are by definition multicultural and global, so much so that some reject the very term as too specifically European. Whatever it is called, the style combines global distribution with infinite local variations. But, like Mediterranean cuisine with which it is closely linked, the Mediterranean garden has a logic of its own.

2) Has this land been used for farming? Is it still productive in any way? Many homes in Mediterreanean climates were originally farms. Their use today by city people is not new: Pliny the Younger made his famous country gardens for escape from duties in Rome. More recent landed gentry kept townhouses while living off their farming estates. Mediterranean tradition never separated elegance from abundance, beauty and productivity. A suitor in Boccacio’s Decameron (1342) sends his lady a ‘few cloves of fresh garlic of which he grew the finest specimens thereabouts in his own garden’! ‘Splendid’ Florentine villas, wrote Edith Wharton, ‘stood close-set among their olive-orchards and vineyards.’ Today wine properties from California to Australia, South Africa or Provence renew this heritage. Even the smallest Mediterranean garden has a fruit tree or vine. These pleasure places for family and friends adapt well to today’s ideals of sustainability and use of local resources. The symbol of this ideal blending of use and beauty, worshipped at times to the point of fetish, is the olive tree.

3) How are house and garden related by the logic of place? ‘The garden was bounded on one side by the house, from which it flowed and into which it ran’ wrote F. Scott Fitzgerald at Cap d’Antibes . The ‘outdoor room’ has ancient Mediterranean variants: courtyards, enclosed or half open; arbours and trellises extending the building. Different exposures invite outdoor eating throughout the day and the year. Vernacular architecture and plantings have always collaborated in climate management: a house sits under the crest and not right on top of the hill, turning its back to prevailing winds, facing the sun. Its hedges and copses serve as windbreaks. Big deciduous trees shade it in summer but let in winter sun. Climbers and vines insulate the walls, often very thick with small openings. They must not interfere with shutters which, carefully regulated, keep indoor temperatures even in all seasons. This logic of place depends on the thrifty management of natural energies—wind, sun and water-- for maximum profit and pleasure.

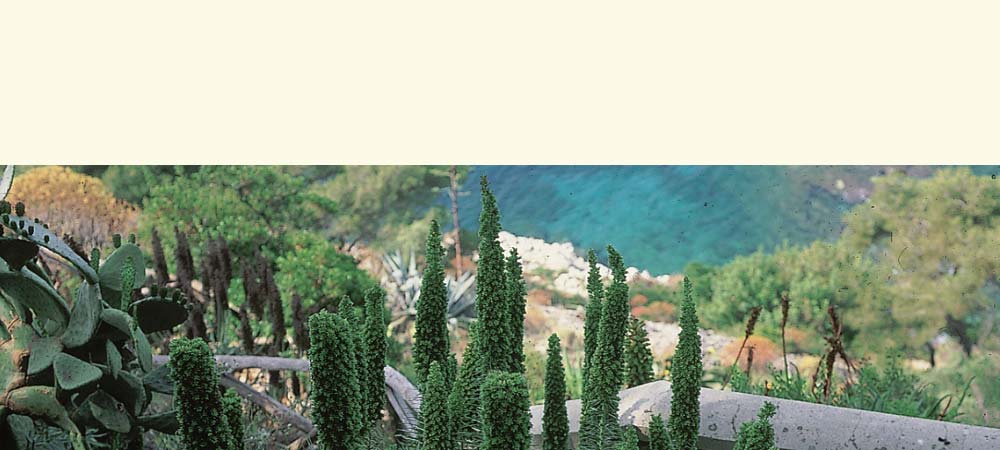

4) How does this garden relate to the landscape beyond? Is its site flat or steep, open or enclosed? Irregular topography lets most Mediterranean style gardens look beyond walls, at least from a roof or upper storey, though city courtyards and Islamic gardens may open only to the sky. Hillside terracing lets a garden be both sheltered and open. Old farming estates sit among their valley lands like the yolk of an egg, their parterres echoing surrounding field patterns. Their vistas are not ‘borrowed’; rather countryside naturally extends the garden in a series of planes from near to far, a feature already appreciated by Pliny. In parts of Spain and North Africa, the view may be from a roof terrace. In built-up areas like the Riviera and parts of California, gardens become secret oases; remaining views are framed like a flat and distant cinema screen, the middle ground carefully blocked out.

5) How is space organized here, and on what scale? Views composed of a series of planes from house to horizon have their vertical counterpart: plantings are layered from low evergreen shrubberies to canopies of deciduous trees, orchestrating year round climate control. Open areas are usually paved or gravel-covered house terraces or courtyards (English-style lawn is an import, though a relatively old one). Sitting and walking areas remain intimate; around them, grey or green shrubs are mounded and grouped from low to higher, with candle cypress or other fastigates, sculpture or pots as accents. Arbours and smaller trees extend overhead, shading walks and sometimes even parterres in summer. This gives a sense of enclosure and intimacy, even in formal spaces, a different feel from stretches of open lawn intended for walking in the sun, or as a platform for viewing borders. Different also from the miniaturization of Japanese gardens, or again from the vast wild spaces of the Americas and Australia. Mediterranean cultural traditions are sometimes called ‘humanist’ in part because of this human scale used in spatial organization.

7) What plants are used here, how and why? Are the plants here lush or the kind that thrive emerging from cracks between rocks? Mediterranean ‘natives’ adapt to dry climates and sparse, poor soil as bulbs, annuals, woody subshrubs with leathery, spikey or thorny foliage rich with aromatic oils. But perhaps acclimatizing rare exotics is the whole point of the garden? Or perhaps the broad-leafed evergreens which thrive here have been clipped to define space and catch the brilliant light? Each region seems to have a favourite, basic building plant--box, pistachia, laurustinus, rosemary, escallonia, or laurel, for example. But whether planty, architectural, sculptural or all three at once, a Mediterranean garden will have year round interest because fruit and foliage (green, grey or mixed) count as much as floral display. Flowers mainly provide accents, in all seasons. Visual appeal may count most, but not exclusively. Fragrance is usually intense, with tactile appeal as well. Such pleasure gardens do not keep you at a distance and may even overpower. Ford Madox Ford called Provence his ‘Eden-garlic-garden’…

7) What kind of light does this garden enjoy at different times of day and year? How does it affect colours, shapes and textures? ‘Mediterranean’ for most people evokes sunshine, hot and intense, and vast blue skies. Broadleaf evergreen foliage lends itself to sculpting light, theatrical contrasts. Weathered stone, terracotta, furry grey foliage absorb light, while leathery leaf surfaces, glazed tiles and water reflect it. Good garden design orchestrates texture as well as colour. Some gardeners like bright, festive, holiday colours in hot climates, but others prefer greys and pastels, taking olive foliage and silver limestone as the keynote. Ochre and terracotta tones in pots, paving or whole buildings may add warm accents to ‘green’ or ‘grey’ gardens. Light sculpting form also links up to an ancient metaphysical heritage influencing contemporary designers like Fernando Caruncho who explains ‘I strive to arrange a space that invites reflection and inquiry by allowing the light to delineate geometries, and this way discover the dynamic symmetries of nature’.

8) Where does the water come from, how is it managed and used? Water, the subject of disputes for centuries, illustrates better than anything else the Mediterranean blending of frugal necessity and pleasure. Stone—heavy, immobile, weathered-- often serves as a foil for water’s quick, light-catching movement, from mountain cascades and ancient irrigation canals to elaborate fountains. Is water in this garden a baroque, extravagant show, a minimalist reflective surface, a wildlife pond? Or is this garden an example of today’s ‘waterless’ approach, inspired by the successful ecosystems of dry scrubland, maquis or garigue? The current mix of economy, elegance, enjoyment and ecological awareness offers a new development on old Mediterranean themes .

9) What is old here, and what is new? How old, how new? ‘Mediterranean’ for many implies ‘ancient’: Lawrence Durrell in Corfu praised the ‘pungent smell’ of black olives as ‘a taste older than meat, older than wine. A taste as old as cold water’. Does this garden deliberately evoke such images? Californians look to Spanish colonial, Provençal owners display genuine Roman ruins--which Greeks find ‘new’! Mediterranean minimalists hark back to Platonic ideas in their exploration of natural form. More prosaically, jetset owners wanting instant gardens pay fortunes to transplant five hundred year old olive trees. Decorators carefully distress wood and stone, rub paint off new shutters, and hide modern technology. Peasant logic applied to home gardening suggests another approach: careful observation of what is already on site with a view to preserving and recycling. Even dead trees can become sculpture. Imagination replaces expense.